When Dieter Döpfer, the founder of music instrument manufacturer Doepfer, decided to launch a brand new modular synthesiser system in 1995, no one could have predicted what would follow. Today, his “Eurorack” format supports an ecosystem of hundreds of manufacturers that have collectively produced thousands of compatible modules used by famous musicians, such as Radiohead, Chemical Brothers and Aphex Twin, and hobbyists alike.

Fuelled by passion not venture capital, most companies in the Eurorack space are neither startups nor established OEMs. Instead – and quite remarkably – the industry remains a long tail of boutique manufacturers, with some of the best-sellers still operating as one-person shops. Inspired by technology that is almost half a century old, and intentionally designed not to scale, these businesses might well be considered the anti-Crunch.

“My happiness is based on developing, not on the amount of sales,” one Eurorack maker told me, after I promised not to name his company for fear of generating too many new orders. “Of course I really appreciate if someone decides to purchase some modules, then I know my work makes sense, but the current sales amount ensures I have enough time for developing”.

He said that increased sales would lead to less time spent working on new designs and more time assembling modules and answering emails explaining why a particular item is currently out of stock. One solution would be to take on an employee or two but the associated bureaucracy would also be an unwelcome distraction.

“That’s not what I like [doing],” he said, comparing it to a friend who owned a single coffee shop and was happy making great coffee and fine desserts, but had subsequently expanded to three coffee shops and is now unhappy. “He’s thinking about selling two of his coffee shops to get his happiness back. More money does not ensure more happiness,” said the Eurorack maker.

It’s the kind of an existential crisis many founders find themselves facing after a company grows to a certain size, but for the makers of modular the reason for existing is often clear from the start. This is certainly true of Döpfer’s own story.

In contrast to the preceding two decades, the mid-80s ushered in the era of digital synthesisers, popularised by Yamaha’s DX7, meaning that instruments based on analog electronics – let alone a modular synthesiser system that had to be patched manually before it would produce any sound – were no longer in vogue. Modular systems from the 60s and 70s, such as those produced by Moog, Buchla, Arp and Roland, had mainly become the domain of vintage instrument collectors, while the modular synthesisers that remained in production were seen as arcane high end products priced well beyond the reach of most musicians.

In those intertwining years, Döpfer had pivoted his company away from analog electronics to produce one of the first digital sampler cards, followed by a more successful line of MIDI keyboards and controllers. However, by 1994 the designer was left feeling unchallenged, and perhaps noticing that second hand prices for Roland’s TB-303 and other discontinued analog synthesisers had begun creeping upwards, Doepfer introduced its first new analog synth in ten years. Called the MS-404, it was mainly designed for Döpfer’s “own enjoyment,” but sold better than expected, creating an even bigger itch in need of scratching.

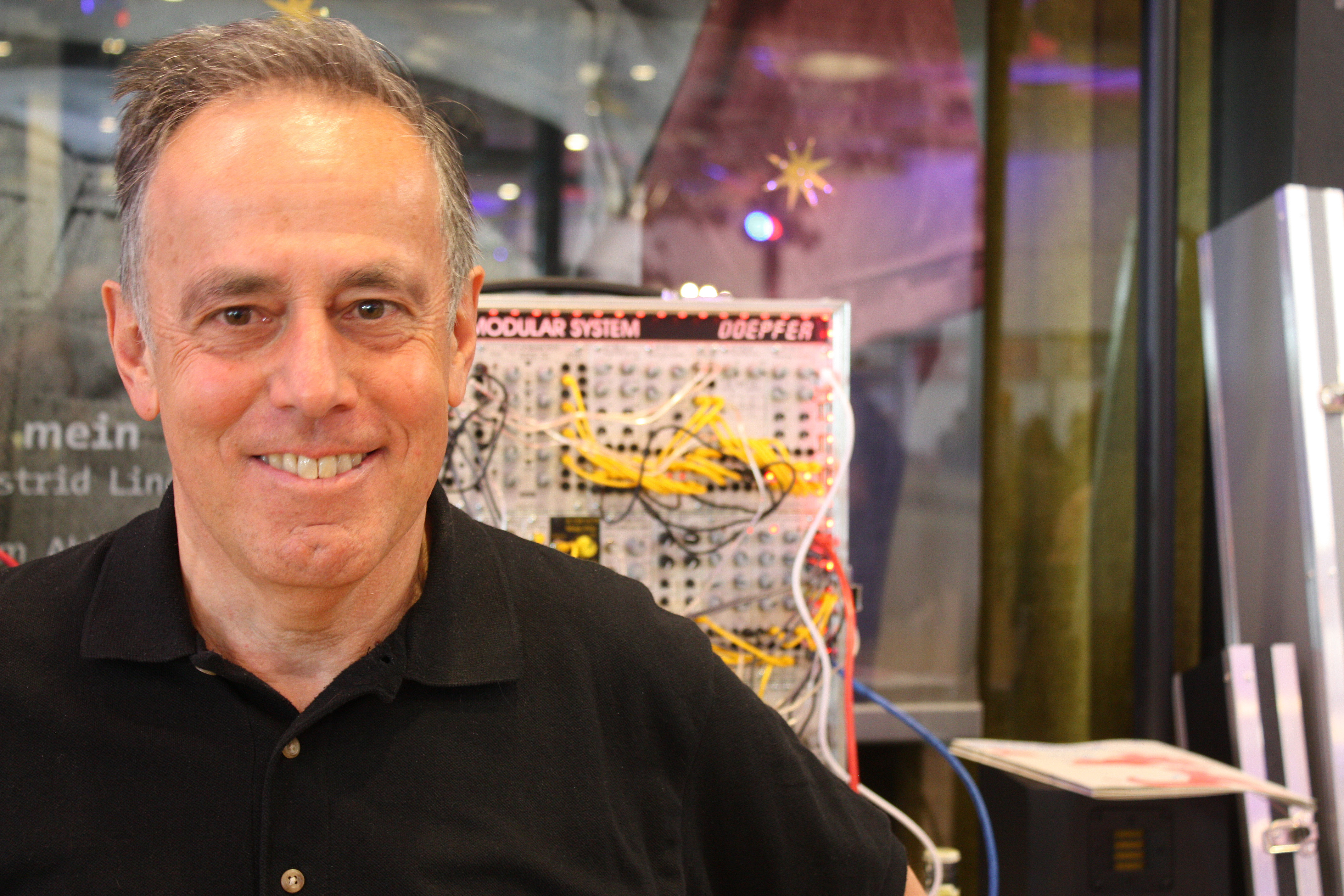

Dieter Döpfer (Photo credit: Theo Bloderer)

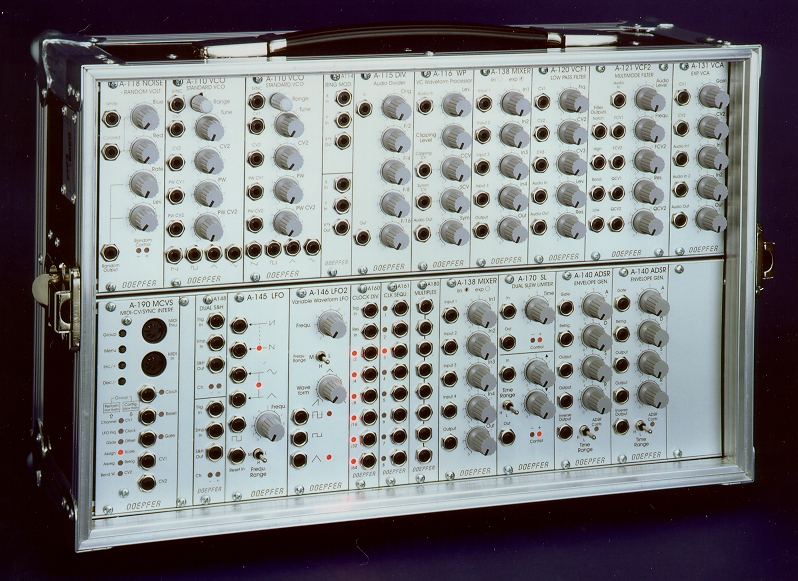

By the following year Döpfer had developed an entire modular synthesiser system he called the A-100. Using repurposed circuits from the MS-404, the system consisted of ten individual Doepfer modules, each fulfilling a specific function, such as an oscillator, envelope or voltage-controlled filter. Just like the modular synthesisers of the past, the A-100 would require the user to create their own instrument by “patching” the modules together. Using cables with a 3.5mm jack on each end that are capable of carrying audio signals and control voltages, the synthesiser’s sound could be shaped or modulated in a vast number of ways and configurations, limited only by the user’s creativity and knowledge of synthesis techniques (or their appetite for experimentation), together with the number of different modules in their system and size of their bank balance.

“The idea was to make it affordable,” Döpfer told me during a call from the company’s office in Munich, Germany. “All modular systems that were available in the past were far too expensive for normal people from my point of view. And so I said, ‘there should be a modular synthesiser available, which is affordable also for normal people, not only for rich ones’. This was the idea behind the A-100”.

Doepfer’s A-100 suitcase

Despite its relatively low cost, Döpfer says the new synthesiser was initially met with bemusement by dealers. He was repeatedly told that nobody was interested in a modular system and that he should spend his time designing something different. “I said, no, I think it’s a good idea, I’d like to have something like that, and that’s why I continued it,” he recalls.

Once again, Döpfer’s instincts were good. When the A-100 made its first public appearance at an industry expo the following year, it was the company’s new modular synthesiser at the back of the Doepfer stand that grabbed most of the attention, relegating its bread and butter MIDI keyboard and controllers to a rather lonely looking affair.

Meanwhile, Doepfer wasn’t the only company developing a new low cost system in a bid to re-introduce modular synthesisers to today’s musicians. Unknown to Döpfer, the British company Analogue Systems had been working on a similar idea.

Purely by chance the A-100 and Analogue Systems’ RS Integrator System 1 were both “3U” in height (based on the 19″ rack standard), shunning the larger and more expensive “5U” design of most existing modular systems. The two systems also took inspiration from the Eurocard standard for printed circuit boards (PCBs) and faceplate dimensions, where width is measured in a unit referred to as horizontal pitch or “HP” for short.

Unfortunately, the exact position of the mounting holes on the modules’ front panels differed between systems, leading to gaps if the two brands were placed adjacent to one another. The power cable configuration was also different, although that was later solved when Analogue Systems redesigned its power supplies to provide Doepfer-style outputs so that systems could be mixed.

Quite brilliantly, however, Döpfer decided early on to publish the specifications of the A-100 module format on the Doepfer website, and in doing so had laid the groundwork for a Eurorack modular synth standard to emerge.

“I thought if the people and the musicians are interested in a modular system, it should be an open system because it was clear to me that we were not able to offer all the kinds of modules the people want to have,” Döpfer told me.

“And so I said I’ll publish everything like the mechanical dimensions and electrical specifications and so on and after, I don’t know, two or three years, the first other guys asked me if it would be okay to offer modules in the same format and with the same design.

“I said, okay, it would be best if more modules are available from other companies, because then the people are more confident in the system, compared to a situation where we would be the only supplier of such modules”.

As modules from third-party makers started to emerge, Döpfer admits he was initially concerned about the effect competition could have on his company. However, as more companies entered the market, Doepfer sales went up, especially since the first generation of Eurorack companies focused on more specialist modules or plugging gaps in the now expanding Doepfer system. “That was really surprising for me,” he says.

“The one thing that Döpfer has done is he’s created an industry out of Eurorack,” says Allan “J” Hall, the founder and designer at British Eurorack maker AJH Synth. “If it wasn’t for Döpfer, there wouldn’t be any Eurorack. And he’s very generous in his approach to it as well. He doesn’t go around saying, ‘well, you know, it was me that started this, I should have all the glory’. There isn’t any of that at all”.

“I was hoping that we could sell the system, I don’t know, maybe for 5 or 10 years or something like that, but now we are close to 25 years,” reflects Döpfer. “And I never thought that it would last for such a long time, and that so many companies and so many modules will be available”.

***

My own journey into Eurorack is less than 12 months old, even though I’ve always loved the sound of analog synthesisers, particularly those used by funk and rock musicians from the 70s. Until recently, the only hardware synth I owned was a relatively basic single voice synth that has remained slightly underused in my home studio. Being “semi-modular” in its design, however, what it did offer was a number of patch points, either for internal pathing or – you guessed it – to external synth modules. One day late last year I decided to build a tiny Eurorack modular case to expand the sound possibilities of the synth.

My tiny 32HP Eurorack case

After purchasing a few modules, mostly second hand via a vibrant used market, it wasn’t long before I’d outgrown my humble 32HP case and a pattern developed familiar to anyone who has caught the Eurorack bug. I upgraded to a bigger case and obsessed over what modules I should buy and sell in pursuit of my perfect system (financial and space constraints permitting). Putting together a modular synth is the epitome of personalisation as no system is likely to be exactly the same. It’s a constant journey of discovery, too, spurred on by the wonderful “what if?” moments that often occur during patching.

It is also a journey that you don’t have to go on alone. The Eurorack ecosystem is well-established. Along with the makers themselves, there are online forums, such as the trailblazing (and oddly titled) “Muffwiggler,” various Facebook groups, Subreddits, YouTube channels, independent stores, and marketplaces like eBay, Reverb and Etsy. The community is generally welcoming to beginners and more experienced users alike, and people who inhabit the scene are often willing to share their experience.

As I immersed myself in Eurorack, I was also surprised to learn how small most Eurorack companies are: from one-person shops to boutique manufacturers of no more than a dozen people. Sure, some makers outsource manufacture and assembly, but it is common for a lot of the work to be done in-house, bar printing circuit boards and milling faceplates. In some ways it is a throw-back to how many hardware industries got started and is a little reminiscent of the very earliest days of the personal computer and the Homebrew Computer Club, except Eurorack is approaching a quarter of a century old.

Despite outward appearances, Döpfer itself only employs four staff (when I emailed the company for customer support, it was Mr Döpfer who replied!). Other examples include the U.K.’s AJH Synth, which has three full time and one part time member of staff, or XAOC Devices in Poland, which employs eight people. Meanwhile, Mutable Instruments, probably the most notorious company in Eurorack after Döpfer, is just founder Émilie Gillet.

“It is very much [a] cottage industry, and I think, purposefully so,” says Ben “DivKid” Wilson, who produces the popular Eurorack YouTube channel DivKid. “I don’t encounter many people that are so driven they want to run it like a corporation, or they want lots of staff. It’s that thing of, you know, if you’re an engineer for a car company, and you climb up the ladder, you’re probably going to end up doing less engineering, and more management. I don’t think anyone wants to let that go. They want to hold on to that reason that they got into this”.

Jason Brunton, who runs Signal Sounds, a Eurorack retailer based in Glasgow, Scotland, likens the makers of modular to the independent record labels he used to work with in a previous job. “The people that run modular companies have a very similar attitude,” he says. “A lot of the companies, it’s just one person’s vision… you can generally speak to the person that made the design, that manufactured it, designed the logo, you know, in some cases, it’s all the same person”.

This is very different to giant music manufacturers like Roland, Korg or Yamaha, says Brunton, where you never have a chance to find out what’s “going on in the heads of the people that make the gear” and only ever hear from sales reps. “You don’t get any insight into why the designers came up with particular ideas”.

***

You don’t have to look very hard to get into the head of Allan “J” Hall, the founder and designer at AJH Synth. Hall has been involved with synths, electronics and music for “more years than he cares to remember,” according to the company’s website, and like many Eurorack makers his entrance into electronics started with building guitar pedals. An interest in synthesisers and electronic music soon followed and for the last 20 years, Hall has been part of the DIY synth scene, including building and modding synth systems both for himself and other electronic musicians. He also spent five years as a service technician repairing and modifying Moog, Arp, Korg, Roland and other analogue synthesisers, along with some Pro Audio design work, including two years designing and building “boutique” valve guitar amplifiers.

“The reason that I went into modular was that at the time no one else was trying to make Eurorack modules that sounded and performed like vintage gear,” Hall tells me. “I was looking for the sound without the reliability issues, and the open architecture of Eurorack allows them to be interconnected in ways that weren’t previously possible”.

AJH Synth’s Allan Hall holding an extended Minimod system

Eighteen months in the making, AJH’s first set of modules was the Minimod released in 2016. The system is a painstaking recreation of Moog’s Minimoog Model D, arguably the most famous synthesiser ever made, and has been used on countless hit records spanning rock, disco, soul, EDM and hip hop.

“The Minimoog Model D… to me was the Stradivarius of mono synths. Then a few people said, ‘will you build me one? will you build me one?’ and I landed up as a Eurorack manufacturer. I wanted this thing to sound as nice as a Minimoog but I didn’t want it to have the limitations that the Minimoog has. If I wanted to try to use it with a SEM filter, I can just patch it in and see what happens. Or if I want to try it with six VCOs, I can patch it in”.

Hall says that designing a module that accurately reproduces the sound and response of vintage circuits that we know and love involves chasing the last few percent. To get to 90 or 95% of the way there is fairly easy and requires taking the schematics from the service manual and replicating it. But it’s the tiny nuances that require real work.

“With designs, it’s not unusual for me still to be working at 1AM,” he says, laughing. “If I’m laying out a complex circuit board then quite often I’ll put in 14-15 hour days. I only stop for meals and to go to the loo and just be full on at it. You find that a lot in electronics, computers and everything else… it’s almost the norm, it’s that human curiosity. The only thing I can’t understand is that some people don’t have it”.

When considering what to design next, Hall says he’s not really “commercially minded” and, as he continues to expand the AJH lineup, he is still building what he considers to be his perfect modular system.

“With something like the ‘Next Phase’, I just thought, ‘I need a phaser’. I don’t really stop and think, ‘is there a market for a phaser?’, I just go ahead and build it anyway… The initial idea really is: there’s something missing in my system, this is what it is, so that’s what I’m gonna do. So it certainly isn’t market-driven”.

To go from design to prototype, Hall says he uses the simulation program LTspice, which models various components so that he can get an idea of how a circuit will perform. He then has a prototype circuit made up and says it typically takes three different prototypes before everything either works as expected or he decides there is a better way of doing it.

Once a module is given the production green light, the front panels are designed, and then manufactured by a company in Germany, with PCB manufacturing outsourced to China. However, all assembly is done by AJH’s small team in the U.K., including SMD soldering and the required calibration of each module.

Allan Hall in his workshop

“We don’t have anything assembled in China,” Hall says. “That’s something I learned not to do fairly early on. If you’re a large company, and you have control, you have someone out there, then yes, by all means go that route. And Behringer have proved that you can go very big and very cheap by doing that. But for small companies like ourselves, you’re very much at the hands of the assembler and they tend to get quite ‘creative’ with the bill of materials”.

He adds that a small change in a component can seem innocuous to a third-party assembler but is often fundamental to a module’s design and the way it will sound and operate.

Distribution and retail, meanwhile, is something the AJH Synth founder is happy to outsource, and, unlike a lot of boutique makers, the company doesn’t sell direct to consumers. “We try to stick to doing what we’re good at. Packing up modules and taking them to the post office or getting couriers to collect them, we can’t do that as well as Amazon or the big box shifters… We just thought, well, if we can get rid of that, then we can concentrate on what we’re good at, which is designing and manufacturing.”

***

“This wasn’t the product of decision-making, it’s really a ‘one thing led to another’ story,” says Jason Coates, founder and sole proprietor of Manhattan Analog in Kansas, U.S.

In 2008 he was working in graphic design and layout, while building a modest studio on the side, and this led him “down the DIY path” by making a few custom panels for available circuits, just for his own use. After he posted his design to a few forums, he quickly discovered there was a need for panel designers within the Eurorack community.

“I started sharing my designs and taking on custom work,” recalls Coates. “At one point I got a request for a simple three channel mixer in 4HP, so I designed what would become the Mix. After sharing that one I had a slew of requests for more, so I did a run of 10. That sold out in hours, so I took the funds and invested in a run of 100”.

By the end of 2011, he says he was making twice as much at his “hobby” than he was doing layout design. “So I quit my day job to focus on Manhattan Analog full time, and I’m still doing it today”.

For production, Coates says these days he generally does runs of 6-12 for an individual module (and always in multiples of three). He concedes that it would be quicker to manufacture in larger batches, at least up to a point, but says he is limited by physical space in his workshop.

“This all still happens in a spare bedroom that’s also shared with my studio,” he explains. “I have started outsourcing a bit more as the line has grown, but frankly I still enjoy doing the work. I feel like it gives me an advantage regarding build quality and it also allows me to be choosy about certain components that may not be available in the SMT, machine-assembled realm”.

For distribution, Coates was able to partner with a number of retailers very early on, but also sells direct through the company’s website, including offering DIY kits for people that enjoy assembling their own modules.

“From a maker’s standpoint, it’s fun to work in Eurorack because there really is that freedom to do whatever you can imagine,” he says. “You can offer small-run or niche products with very little risk, and there’s not a lot of overhead involved since the ‘bones’ of the systems, such as cases and power supplies, are already widespread in the market”.

In other words, it’s partly the modular aspect of modular that makes Eurorack an industry that attracts long tail businesses. “Even as a student you are able to design one single module,” says Döpfer. “You can design a very limited project as there is already a pool of thousands of modules which can be used in combination with your special module. That’s very different to other markets”.

“The other aspect that makes it fun on the supply side is the tight-knit community that goes along with it,” adds Coates. “That direct connection with the customer base is probably as important to the makers as it is to the musicians”.

***

“Oh, I gotta want it, first and foremost,” says Garren “G-Man” Morse, founder of G-Storm Electro in Oklahoma City, U.S. “There’s something about analog circuits I really go for. And luckily, others have wanted the same things. So that’s all working out nicely”.

A trained engineer and architect, Morse found himself out of work after the financial crisis hit in 2008. While he was looking for a job he studied up on electronics, which began with “circuit-bending” an old Casio keyboard.

“I was buying up used textbooks, Forrest Mims guides from Radio Shack, and studying old synthesiser service manuals and schematics,” he tells me. “I built a few kit things. When I felt confident enough, I got hands-on with synthesiser restoration and flipping synths. And eventually bought a small Eurorack system. Little did I know where it would lead me”.

G-Storm Electro’s growing lineup of Eurorack modules

He wouldn’t go on to launch his own Eurorack hardware business until 2017 and in the interim period, amongst other jobs, tried his hand at writing and selling software instrument plugins based on his love of vintage string synthesisers, such as the Roland VP-330 and Logan String Melody. He says he soon realised that “the plugin game is all about how many platforms can you satisfy,” and decided it wasn’t for him. “I just wanted to make these plugins once, not 12 times over”.

“Hardware has a very satisfying, tactile interaction you can’t get with software,” adds Morse. “Hardware has this physical presence that commands your attention and rewards the senses in a very engaging way”.

He concedes, however, that he still spends an estimated 60% of his time at a computer with module design, cost analysis, ordering, social networking, client interaction, and promotion. “But it feels more rewarding to me,” he says.

The soft aspects of running a Eurorack business, including social media promotion, applies to every company, no matter their size. However, for businesses like G-Storm Electro, which don’t have a distributor or retail partnerships, it is even more important. Currently, the only place you can buy G-Storm Electro modules is from the company’s store on Reverb.

“My appreciation for the internet and forums are greatly magnified when I think about musical instrument reps that promoted their product by jetting around the world to various dealers, or the DIY synthesizer instructions that were published in magazines,” says Morse. “The access to products, information, and specialised electronics components were relatively limited compared to now. On a frugal budget I don’t have such luxuries to jet around the world for promotions. So I wing it on social media, YouTube videos, and good old fashioned word of mouth. I love Reverb, their no-nonsense business acumen is so close to mine. Their fees are very fair, and I really do feel I have my own store within a larger store. It’s been indispensable”.

As not every module sells equally, Morse’s strategy over the last six months has been to diversify by launching new modules rather than simply replenishing stock of his previous designs. He’ll typically make batches of about 5 or 10 modules at a time, which he says are hand-crafted in a “work-at-home scenario”. His latest creation is a faithful Eurorack adaptation of the main features of Roland’s revered SH-101 synthesiser. Earlier in the year, Morse also adapted the filter circuit found in the Arp Odyssey Mk1 synth (dubbed “G-Storm Electro 4023,” I purchased number 3 of the first 5 modules produced).

“My operation is small and nimble,” he says. “My space and budget for parts, assembly, and inventory on hand are meagre. So I’m always working within those confinements. I can envision opening shop someday, or possibly selling in stores, when I’m able to move more units. As long as I can keep up with demand, there is no need to outsource as of yet. I’m having fun with it. If it stops being fun, then I’ll be calling for help from someone or move on to the next thing”.

***

“My name is Émilie and I am Mutable Instruments’ product designer, hardware/software engineer, sales person, and customer support representative,” reads the Mutable Instruments website. “Mutable Instruments has, by design, no employees! Just me!”

Another one-person shop, Mutable Instruments punches above its weight like no other Eurorack maker. Over the years, the company has designed a series of innovative and best selling modules, proving that digital has a well-earned place in Eurorack and, as one Reddit user put it, “is just as elegant and organic as analog”.

Based in Paris, founder Émilie Gillet has a background in software engineering, having previously worked for tech companies such as Google, Last.fm and MXP4. She first gained a reputation within the music-making community after developing “obscure” music software including a granular synthesis tool for BeOS, and Bhajis Loops, a Digital Audio Workstation (DAW) for PalmOS. However, the precursor to Eurorack came in the summer of 2009 when Gillet started building and eventually selling DIY kits.

The first of these was the Shruti-1, a hybrid digital/analog desktop synth, which initially sold at a loss before being sold for profit in September 2010. A year later, Mutable Instruments the company was born.

“I quit my main job in February 2012 because the company I was working for was going nowhere, while Mutable Instruments’ first quarter showed that I could live decently off the DIY kits even if we weren’t quite there yet,” Gillet tells me.

The first four Mutable Instruments modules were designed simultaneously, with Braids, a “macro-oscillator” that digitally modelled a vast range of synth voices and timbres, proving to be the most popular.

“I made an informal demo of Braids at a local shop and everybody agreed that it had a lot of potential,” she recalls. “The other modules were considered less original, or seemed to fill smaller niches. But Braids’ appeal seemed to be universal”.

Because of Gillet’s reputation designing DIY kits and music software, unlike other modular companies, Mutable Instruments didn’t have to overcome a “cold start”. This meant that retail partnerships were forged early on and the company only needed to sell direct for a short time. Today Mutable Instruments modules can be found in most independent stores and big box-shifters in the U.S. and Europe.

A selection of Mutable Instruments’ modules

Gillet typically prototypes new digital modules by writing C++ code and a command-line tool to process or generate audio files, or she’ll write a patch for the visual programming language Pure Data. To get more of a feel for how the software will interact with hardware, she may write an alternative firmware for an existing module so it’s directly testable with CV inputs and physical knobs.

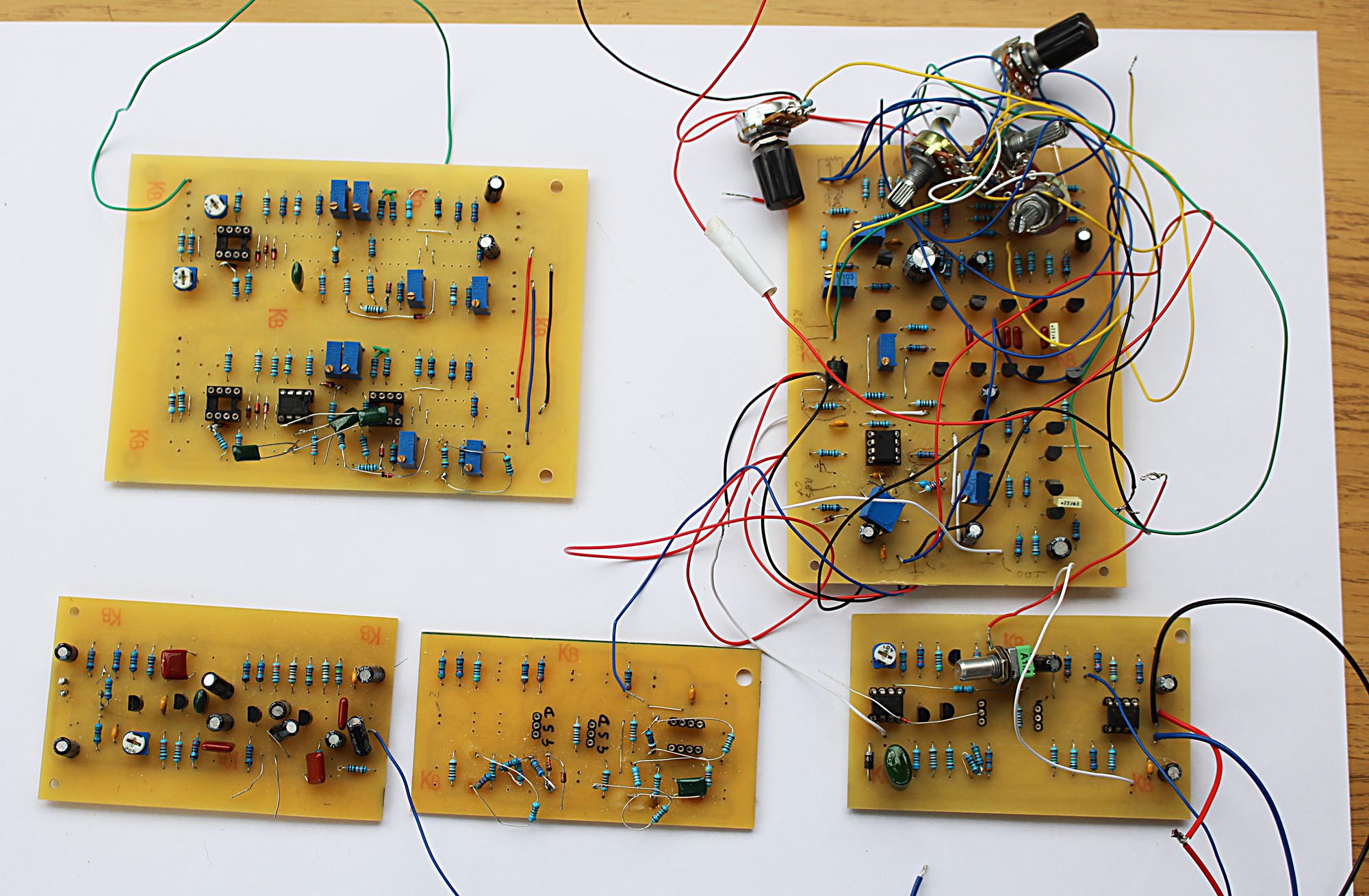

Analog modules are prototyped on a breadboard, sometimes with interconnected through-hole PCBs. “I actually made a very large through-hole PCB for my latest analog design,” Gillet explains. “It’s easier for me to replace components, build little networks of extra diodes, capacitors and resistors in 3D above the board when it’s made of large parts. I maintain in parallel LTSpice simulations and python notebooks with all the calculations for part values, cutoff frequencies, gains, etc”.

Next the schematics are inputted into the PCB design software Eagle and discussions are initiated with UI designer Hannes Pasqualini, with whom Mutable Instruments has a long-standing partnership. “This is a dialog, features may be added or removed to make the panel more symmetric or elegant,” says Gillet.

Finally, the design is sent to a company in Germany that specialises in manufacturing and assembling prototypes, and front panels are ordered from Mutable Instruments’ production partner.

“At this point the prototype looks good and works well enough to fool people into thinking it’s a finished product. Then there’s a rather long playtesting phase. Just messing around with the module to get a feel for how long the excitement lasts, sending the module to the only tester who actually finds bugs, and for digital modules there’s a lot of balancing and curation.

“I [then] let the project rest for some time, and if I still feel excited about it, I move forward”.

Moving forward involves FCC/CE compliance tests, writing a user manual, and taking photos for the Mutable Instruments website and retailers. This is followed by a pre-production run of 20 modules to check that everything runs smoothly.

“I tend to be present at the factory the day they are made,” explains Gillet. “They are [then] thoroughly tested and sent to people for some additional field-testing. At this stage it’s no longer about getting feedback about the design, just making sure unexpected things won’t happen in very diverse and wild configurations”.

If there are no reports of problems for 3 months, a much larger order is placed with the manufacturer, typically between 480 and 980 units, while a single module on average sells 3,000-5,000 units over its lifetime. Plaits, the successor to Braid, has so far required eight or nine batches of 1,000 units.

“Obviously I don’t build anything with my own hands,” says Gillet. “I receive the modules in their box, ready to ship to dealers. My contract manufacturers take care of everything i.e. board assembly, panel assembly, testing, and packaging. Thank god for that”.

***

If you go back and read or watch various interviews with Döpfer, something resembling an old joke emerges. For years the father of Eurorack has been saying that he thinks the bubble may have finally reached its peak, only to concede that the industry has grown even bigger the following year. However, throughout many of the interviews for this piece, there was a general feeling that growth in the last year or two may have begun to slow even if the market is more saturated than ever.

“I don’t think it’s at its peak, but maybe a slight plateau in its growth,” says Wilson, who recently designed and launched his own “DivKid” branded module in partnership with Befaco, a Eurorack maker based in Barcelona, Spain. “There’s definitely larger growth in people making modular devices than there is the market… Sales haven’t increased as much as the outside world looking at modular may think it has”.

“If I had to put my finger up in the air and sort of take a guess, I would say things are about static at the moment, definitely not the growth that was there about five or six years ago,” says Signal Sounds’ Brunton. “The [other] thing is that the mainstream retailers have moved into modular quite a lot, so it’s actually quite difficult to tell if modules are consistently selling. It may well be that it’s selling consistently it’s just selling less per individual retailer.

“People always want the new thing. And the other issue is, there’s always a new thing”.

For anyone interested in creating the next new thing and starting their own Eurorack business, what advice might existing makers and retailers have to offer.

“You have to know the scene,” says Matt “Matttech” Preston, founder of Matttech Modular, an online retailer in Manchester, U.K. “Immerse yourself in the scene, know what’s popular and then think whether you could either add something, make it smaller or make it cheaper… Come up with something that you can see there’s nothing like it out there”.

Mutable Instruments product shot

Another aspect to watch out for is the visual representation of your module, which, Preston says, too many makers initially overlook. “You need front on photos, you need demos — video demos, ideally, but at the very least audio demos — and you need all the text and information to be there”.

“You should focus on your idea,” advises Döpfer. “If you have an idea which you think is great, you should follow your idea and stay on track. Don’t look to the left. Don’t look to the right. If you are sure that you have a good product, you really should release it”.

AJH’s Hall says it is still possible to have a successful Eurorack product but you need to have something that’s different and that people want. “If you’re lacking in either of those, then all you’re gonna do is waste a lot of time and certainly a small amount of money, and possibly a large amount, depending on how you do it,” he says.

The first AJH Synth Minimod prototype PCBs

“Decide straight away what route you want to go down,” advises Brunton. “Do you just want to make 10 of them, or 20 of them and sell them direct? Or do you want to turn it into a business? Make the decision at the beginning and stick to it. And if you’re going to turn it into at least a part time business, get your pricing right at the beginning. Factor in not just your time and cost on components, but factor in a retailer’s margin and, if you can, a small distributors margin”.

Mutable Instruments’ Gillet argues that quitting the day job too soon is a rookie mistake, and instead you should aim for organic growth and “don’t expect things to work out right away”. She also warns that you could be “too late to the party”. Rather than releasing one more module, consider other clever ways of contributing to the Eurorack ecosystem, such as cases and power distribution, patch management, and interfacing with other tools.

“At this point in time I would advise caution,” echoes Manhattan Analog’s Coates. “If you’re going to get started now, you have a lot more to worry about than we did a decade ago when a hobbyist with some skills like me really could add meaningfully to the landscape… With fewer gaps in the market that need filling, you’ll need to be an order of magnitude more innovative and creative”.

“At no point in creativity can you can you say it’s all been done,” counters Brunton. ‘Everything’s been done, we won’t paint any more pictures or write any more books, because what’s the point?’ Within modular, there’s room to either reinvent the wheel, which is taking old ideas and doing them slightly differently or there’s infinite different combinations you can have just by taking an idea and plugging it into another idea. So sometimes it’s just combining certain things in one module, and then at other times it’s making interesting ideas more accessible”.

Which, perhaps brings us full circle, back to the very beginning when Dieter Döpfer took an old idea and made it infinitely more accessible.

“I’m still excited to go to work every day and I’m very happy,” he tells me. “So as long as this lasts, I think everything’s okay for me and for our company. We had ups and downs during the last years, but we are such a small company we are not that much depending on if sales increase by 20% or go down by 10%. For us, it’s important that it’s fun every day.

“We also have a lot of friends here in our neighbourhood, which use the modules in their system and also play live on stage. It’s a lot of fun for us if we can go to a concert where we see that 50% of the equipment on stage has been manufactured by our company. That’s something that’s incredible. And that’s why we still love this job”.

Dieter Döpfer (Photo credit: Theo Bloderer)

The Eurorack allure (in their own words):

“Modular is a spectacle. It is producing crazy sounds, patch cables going everywhere, flashing lights, and this beckoning conglomerate of knobs and faders. Musical instruments, guitars, and drums are already very personal in nature – it becomes a part of you, an extension of your spirit. Then add to that what modular brings, a highly customisable instrument, tailored by you – for you. I think modular enthusiasts are mostly hungry to discover things, new and old, in the realm of electronic sound. The more you discover, the more it feeds into the imagination, thus sparking curiosity to discover more – it is a virtuous cycle”.

— Garren “G-Man” Morse, founder of G-Storm Electro

“One of the great things about Eurorack is there is a choice… It’s different things to different people. That’s why there are over 200 manufacturers and each of them have their own approach”.

— Alan “J” Hall, founder of AJH Synth

“There’s some separation for me between sound and music. I think you can explore sound for sonic qualities, and learn and engage in that, almost separately to music. Of course, there is a huge crossover and a big grey area between the two. But I just really enjoy all aspects of it, just exploring sound, learning on a technical level, making music, it just felt right, for some reason”.

— Ben “DivKid” Wilson, producer of the DivKid YouTube channel

“It attracts and appeals to non-musicians, by which I mean non-standard musicians. So there’s a significant portion of people who get into modular and Eurorack who are coming from completely outside the industry, which means they haven’t really played a keyboard or guitar or any other instrument before”.

— Jason Brunton, founder of Signal Sounds

“To be your own mad scientist; the tangibility of tweaking knobs with obscure descriptions, making indicator lights flash to patterns clear to yourself but mysterious to the onlooker, to building the musical instrument of your own design without any limits (besides the size of your wallet)”.

— Tom Verchooten, DIY-er and founder of ThreeTom Modular

“From a musician’s perspective, I think the allure of modular synthesis is the absolute lack of limits, the near-infinite customisability. There are modules out there that can help you make nearly any sound you can imagine (and many more besides) and that’s very attractive. On top of that, modular synthesis is just plain fun. There are always moments of serendipity where the instrument will surprise you, and in my case at least, that’s irresistible. It’s also very satisfying to work with such a tactile instrument. Software is fine, I’ve used (and still use) my share like anyone else, but it really is missing something compared to working with real knobs, patch cables, touch interfaces, etc”.

— Jason Coates, founder of Manhattan Analog

“It felt for me like a very natural thing to do because with my electronics background, we are used to having components and wiring them together to create something bigger. Modular was a perfect fit for me… I feel flexibility when you can connect things in the way you want”.

— Dr. Leonardo Laguna Ruiz, founder of Vult

“I think the main difference to another instrument is that you don’t have an already built instrument. If you go to the guitar shop, you buy a guitar and then you have the final instrument. For a modular, it’s totally different: you have to build your instrument first. It means you have to collect the modules and install them into the case and so on before you can start using the instrument. So that’s totally different compared to other instruments. That first creative process is to design the instrument. So that’s a lot of fun from my point of view.

The second is that, in most cases, you have a very special instrument, which is probably the only one in the world unless you buy a standard system. But I think 90% of all the modular systems are totally mixed with multiple modules from different manufacturers. Each system is very unique”.

— Dieter Döpfer, the father of Eurorack

from TechCrunch https://ift.tt/2o5sEFN

via IFTTT